Interview: Danish DJs Den Sorte Skole

Stitching together thousands of samples from around the world for the album Indians and Cowboys, plus a CH track premiere

John Oswald, Girl Talk, DJ Shadow and even Pogo are recognizable artists who made their name creating new music exclusively from samples. Copenhagen-based collective Den Sorte Skole distinguishes themselves not just because of their numbers—their latest album Indians and Cowboys (releasing as a free download next week from their website, the only way to avoid legal issues) features thousands on thousands of samples off 350 records from 75 different countries and multiple decades—but rather because of the message. This isn’t music for pure consumption or physical catharsis, but for discovery and understanding of our place in time, and in the world.

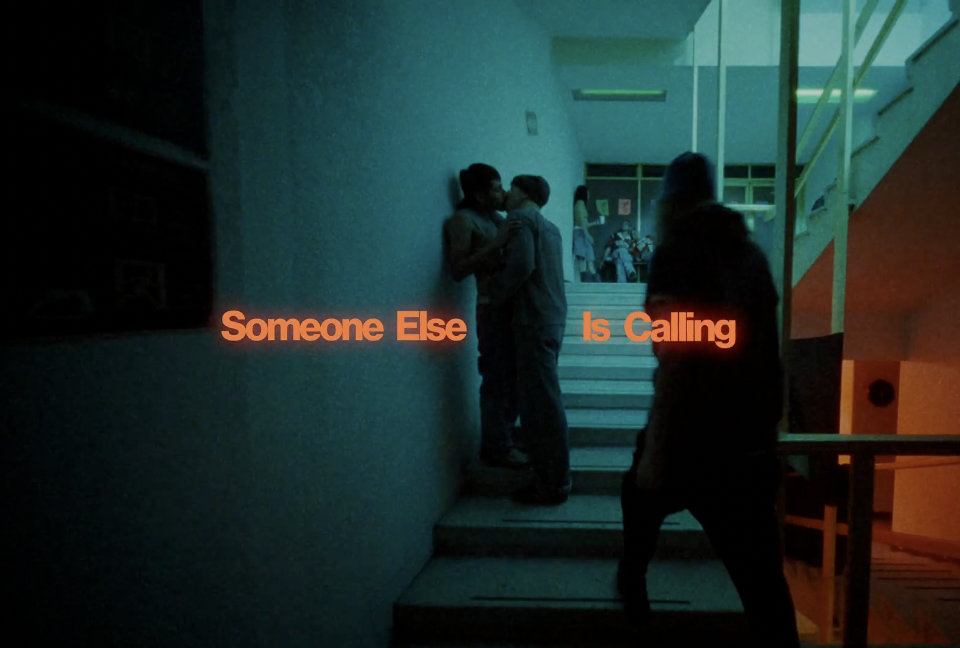

Below, CH premieres “El Chark” from their new album and asks DJs Simon Dokkedal and Martin Højland (the third founding member Martin F. Jakobsen is on hiatus) how an album like this gets made and performed and, most importantly, why it exists.

How did Indians and Cowboys differ from 2013’s Lektion III in terms of production?

Martin Højland: In short, we are using far more samples this time and made some more sophisticated compositions and better sounding productions. But still, this is a 100% sample-based album. We have had a different process though. First of all, we have been building on the foundation that we made with Lektion III and therefore didn’t need to invent everything from scratch. We also had a huge sample archive to begin with and have progressed in production and composing skills. The latter, especially through our residency as guest composers at the National Danish Chamber Orchestra and the Copenhagen Philharmonic Orchestra that started last year and will run until our last symphony in 2018.

Our ability to work with smaller and smaller bits and pieces of sound has also made us capable of liberating our tracks more and more from the character of the original samples. At the same time, we wanted to do a more rough and raw album than Lektion III, which was a bit more like a polished fairytale. In that sense, this album is more challenging, but also more reflective of the world we live in—aggressive, messy, beautiful, noisy, calm, melancholic, romantic, happy and sad at the same time.

Are all of the samples pulled from vinyl that you personally own?

Simon Dokkedal: We own almost all the records that we sample from and [our] collections are getting too big after 20 years of digging. Sometimes we start composing with MP3s, but because of their crappy quality we always end up buying the vinyls from around the world. In some cases we are not able to find the vinyls though—then we get help from collectors that make recordings for us and send them. It is a very beautiful thing, we think, that people from around the globe take action and bring together sounds for “our” albums.

Many of the samples come from albums from foreign countries and different time periods. How are you able to find these albums? Does your music become a historical and cultural lesson in a way?

SD: Definitely we feel that our music possesses some kind of quality as a historical and cultural lesson or document. This is why we always release a full list of the original tracks that we have sampled. By doing that we try to open our music to people and hope they will dig in and pursue some of all the musical treasures that we have found through our work. We could never clear all the samples we use, but we can make sure that the original artists are credited and that some of our listeners will find the original music and prolong its life. The stuff that we sample is completely off the big mainstream radar, so our work is an attempt to keep some of the forgotten pearls of our common musical treasury alive.

We could never clear all the samples we use, but we can make sure that the original artists are credited and that some of our listeners will find the original music and prolong its life.

We find the albums primarily through the internet. The internet has so many amazing blogs written by true vinyl geeks, uploading obscure and impossible to find albums from around the world. Some of all these blogs are listed in our credit list in the Lektion III release. These places are goldmines for people like us. Only problem is that we then have to find the music on vinyl afterwards, but that is part of the game. Otherwise we love to visit secondhand record shops when we travel. Nothing beats finding an obscure record “by hand” and then finding a killer sample on it afterwards!

What is the composition process like—to what extent are the samples manipulated?

SD: We rip all the vinyls to digital and compose the music in Cubase. However we don’t manipulate our samples very much. We do some equalizing, reverb and a little distortion and other effects once in a while, but we don’t pitch the key of the original samples. It’s a goal for us to match things across time and space, but to keep the original expression of the material—to keep some transparency in the material. A lot of musicians sample, and a lot do it in a way, where they manipulate the samples as much as possible to create a new sound. Nothing wrong with that. But we try to make sample-based music that sounds like it wasn’t sampled. Music that crosses time and space, bringing together completely different styles, genres, cultures and colors in a way that sounds like it was intended to be so. Full of references to music that is out there, but still with its very own character—a bit like tuning into a radio station from a parallel multicultural musical planet, where genre is nonexistent.

Today, a lot of music sounds clean, perfect, almost too good.

However, matching the samples without pitching and heavy manipulation takes a lot of time. We have built an enormous archive over the years, which is divided into categories like instrument type, tempo but also key. But within the E minor chord, you can have so many different pitches. So the challenge is to find stuff that really play together, rhythmically, sonically and key-wise. A gamelan player from Bali didn’t tune his instrument to the same E minor chord as a synth player from Germany! However, one of the strengths with sampling as a method, is that you bring in a lot of resistance with the material. The samples have character and noise from the original recording session, vinyls maybe have scratches, etc. And this gives authenticity to the sound. Just like when we are matching instruments that are not perfectly tuned with each other. Today, a lot of music sounds clean, perfect, almost too good. In the 1970s, that we love to sample from, Auto-tune and computer production wasn’t out there for everyone to use. Instead they had skills, heart and the open-mindedness to embrace imperfection. Qualities that we are fortunate to bring into our music through sampling.

I might be able to make a rough guess, but what does the album title Indians and Cowboys reference?

MH: Well, first we turned around the order of things. The Indians came first, and then came the settlers and the cowboys. However, we—in the west—tend to see ourselves as the central point of all development and this ethnocentric attitude towards the rest of the world is often integrated in our language (cowboys are usually mentioned first). The next interesting thing is, that the Indians (and indigenous peoples from around the world), from whom we stole the land, didn’t believe in land ownership. According to them, we, as human beings, can only borrow the land, that belongs to the nature.

For us, this is a clear analogy to our work and the music that we are sampling. We are borrowing from our common musical treasury, creating and communicating out of respect to the original artists. We want to question the blind belief in private property rights within the music industry, and also in a broader sense. Private property rights and intellectual property rights are some of the most defining structures of our society. We are not completely naive and think that we can just skip private property rights, but the problem is that our system is built on the false proposition that our juridical and economical system is fair and coherent. It isn’t! For instance, the price I am paying for my Nike shoes or my Mercedes Benz—I wish!—is not reflecting the pollution costs these products generate when they are produced or used.

The future is full of complexity and multicultural interdependency and we have to deal with it, instead of clinging to outdated perceptions of ownership.

So to believe and tell ourselves that we have the right to own something and that that something, has a fair price that I can pay to own it fairly, is absurd. The global system today is far too complex for the systems we have built. And speaking of property rights and fairness in the same sentence is unfortunately naive. Take the situation with all the refugees seeking to Europe these days. I don’t feel or believe that I have a greater right to live on Danish soil than a refugee family from Syria. I was lucky to be born in Denmark and people like us, who have more than enough, should make a larger table instead of building a higher fence. The future is full of complexity and multicultural interdependency and we have to deal with it, instead of clinging to outdated perceptions of ownership. And interdependency and the meeting between cultures is also what the title and this album is about. East meets west, north meets south, conflicts and peace, chaos and harmony.

What does it mean to you to be able to create something new from thousands and thousands of samples created by artists? Can you have full creative ownership of your album, regardless of what iTunes thinks?

MH: We don’t feel that we have the full creative ownership of this album. We have built this album, standing on the shoulders of the thousands of musicians around the globe, that have lent us their sounds without knowing it. We feel connected to these people and feel that we are the composers and conductors bringing together an enormous multi-headed ghost-orchestra. You could say that our music is made by a band with members from more than 75 different countries on six continents—probably the most eclectic band in the world—with a sound way bigger than two pale white guys pressing buttons on a sampler.

Are you able to perform an album like Indians and Cowboys live?

SD: We could never recreate the album live, soundbite by soundbite. We play live with a combination of Ableton, turntables, MPDs and effects machines. Basically we have some backing tracks running and then play as many layers as possible on top, to create the live element. The idea is to give people a sense of how the music is made, by building as many layers as possible on stage with the risk of everything falling into pieces.

Apart from the album, how is your current residency at Copenhagen Philharmonic Orchestra and what do you hope to accomplish by its end?

SD: In February 2016, we will premiere the second symphony of the trilogy that we are doing. The first symphony is streamable from our website now! The residency is a very, very big thing for us. We learn a lot—not least from working with composers Karsten Fundal and Karl Bjerre on this—and we feel that we have been giving an important chance to fill a gap in what classical music is offering today. Classical orchestras around the world really need to start communicating with the younger generations—otherwise they won’t survive the next 30 years. We are trying to help to formulate some possible ways forward by bridging different musical worlds and that is super interesting. Having an symphonic orchestra playing together with samples of Lebanese nuns singing and Amazon Indians drumming is a crazy idea, but it works overwhelmingly!

I’m curious to know how you two enjoy music outside of the studio, for pleasure. Is this possible at all, or are you straining your ears to hear a new possible sample to use?

MH: You are very right, unfortunately. It is very hard not to always listen for the next thing to sample. But we do enjoy music very much. These days I am listening a lot to Australian band The Necks and old Indian raga music—the latter is perfect for relaxing and building Lego with my two boys.

Indians and Cowboys will be available for free download on Monday, 26 October 2015, directly from Den Sorte Skole’s website. The album will also be available on vinyl and CD.

Images courtesy of Kristoffer Juel Poulsen, album artwork by Claes Otto Jennow