Studio Visit: Trail Map Artist James Niehues

On painting the slopes, from trees to terrain, with no digital software

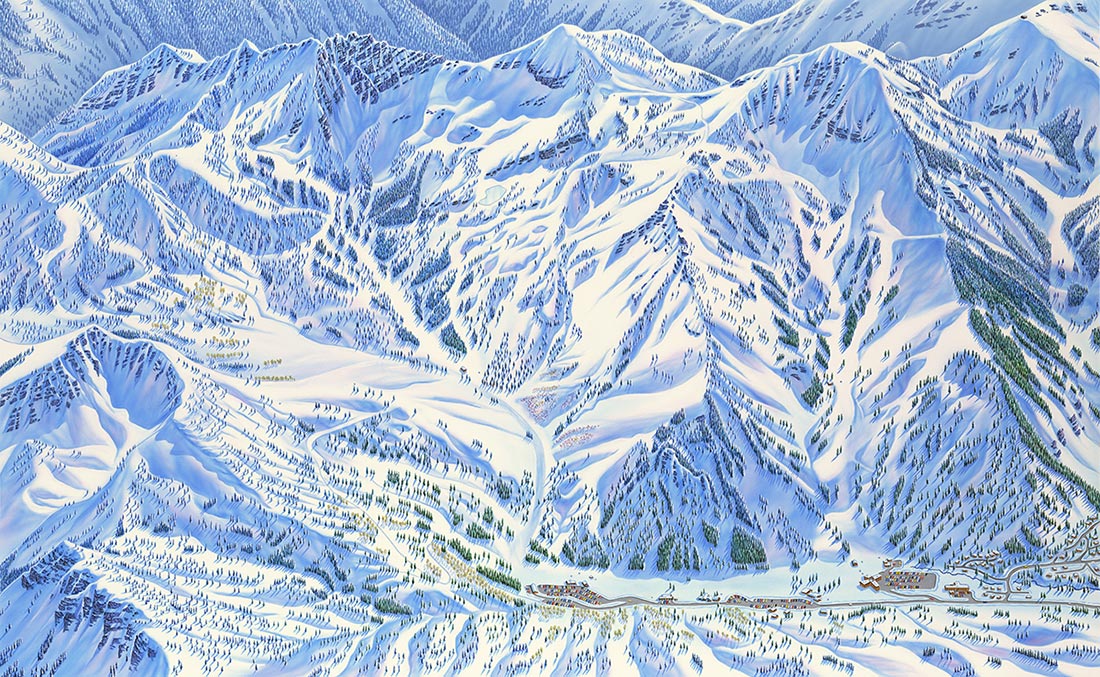

If you’ve ever grabbed one of the colorful trail maps stocked in ski lodges, or affixed to the chairlift bar, there’s a good chance you’ve seen—and used—the work of landscape artist James Niehues. Niehues (who goes by Jim) is one of just a handful of people who have mastered the art of capturing the workings of mountains for those traversing them, having succeeded industry greats like Bill Brown and Hal Sheldon, and paving the way for promising young artists making the reverse-evolution from computer-generated imaging to hand-painting. We made the trip out to Niehues’ home in Loveland, CO, where he works in his basement studio (alongside his wife, who is an accomplished quilter), to learn more. He walked us through the process, from Cessna trips, to sketching, to working with clients on the most beautiful and useful interpretation of nature’s ski peaks.

How do you “capture” a mountain in order to draw it?

Usually I use a small plane, a Cessna. Occasionally I’ll get in a helicopter, I just prefer a small plane. It gets around better, and gives you more variation, while a helicopter tends to hover and sometimes you concentrate on getting a particular shot instead of getting the whole thing. With a plane you fly by, you’ve got to just be shooting information, and that’s what I do, I don’t worry about composition at that point, I’m just gathering the information that I’ll use. I’ve got a digital camera, and we just shoot a bunch of pictures. There’ll just be photographs of the details on the ski runs on a portion of the mountain, so you may take in a lift pod or you might take in a certain area that seems interesting.

What kind of digital camera do you use?

I just switched from Canon to Nikon. The D7100 has Active D-Lighting which adjusts the exposure before shooting each shot to optimize the dynamic range (proper exposure in both shadow and highlight areas). I am always shooting high-contrast with snow, so it’s very nice to have this adjusted while shooting instead of adjusting every shot afterwards in the studio.

In terms of your method of flying over and capturing the actual map, and what you’re going to draw, is that a technique that you’ve changed, or that’s been honed over time?

I don’t think so, I have had people come back and ask me what kind of software I used. I use a software up here [points to his head]…. The real software. I mean, the artist before me did it this way, and it’s the best way. Just get up there and get some visuals. It’s all a representation anyway. I don’t care about being exact.

Did you study under the previous artist you mentioned or just took over?

Not really. Yeah, I just kind of took over. Bill [Brown] wanted to retire, and he had a project—the backside of Mary Jane in Winter Park—in his office to be done, and I just dropped in one day. We got to talking, and I showed him my portfolio, and he said, “Well, I do have this one project and I’ve got plenty of time, so if it doesn’t turn out right, I can go ahead and do it over then.” So he gave me that.

How did you decide you wanted to do this type of work?

I’ve always wanted to be a landscape artist. I’ve always loved landscapes. I always admired the trail maps by Hal Sheldon, Bill Brown. So I relocated to Denver, and in looking for work to do, I decided to look up Bill Brown. I figured, it was a shot, I didn’t know—maybe he needs somebody to paint whenever he gets overloaded, so I thought I’d do that. And it really turned out that my timing was absolutely perfect, and then Snow Country Magazine was a brand new magazine, and within a few months after I met Bill they contacted Bill to do the center spread, and Bill referred them onto me. So I instantly had a magazine that was featuring my art, that was going out directly to the clients that I would be servicing. All of a sudden I was so busy I didn’t know which end was up.

Did you grow up painting and drawing and doing landscapes?

Oh, yeah. I was ill in the ninth grade with nephritis, and I had to remain on my back, in bed, for three months. So my mom bought me an oil painting set, and I painted oils from my bed, which was pretty messy. I didn’t have photographs, I’d just paint to pass the time. That’s what got me started into oils.

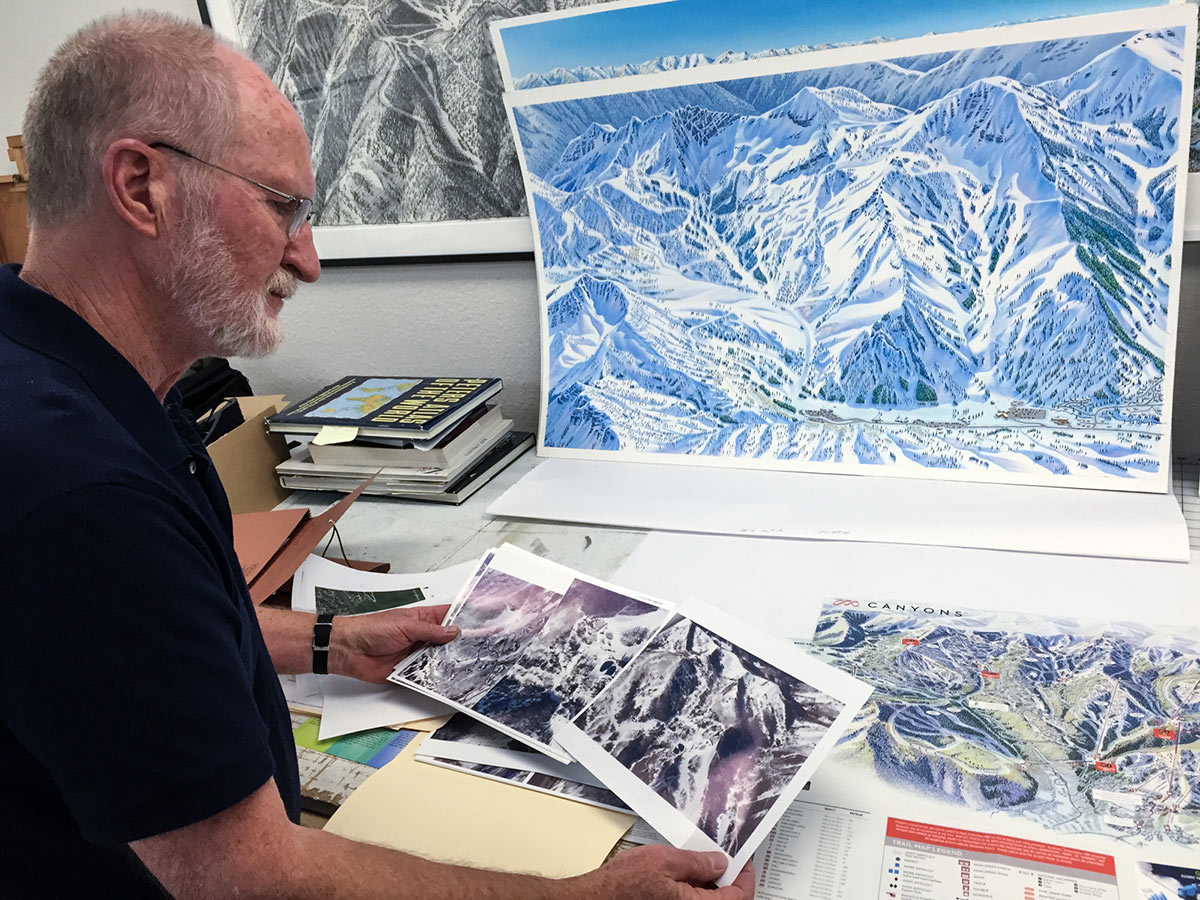

Can you walk me through the steps of creating a map once you’ve shot the mountain?

Basically nowadays I use Google Earth to help me get the angles and so forth of the mountains that I’m doing, so I’ll take the Google image and I’ll rework it and I’ll change the angles of the lifts. I’ll put in a rough of the trails and make sure I can get them all in there, and just develop it and turn the lift direction in a way I can get the most runs running down-page, to get the steepness.

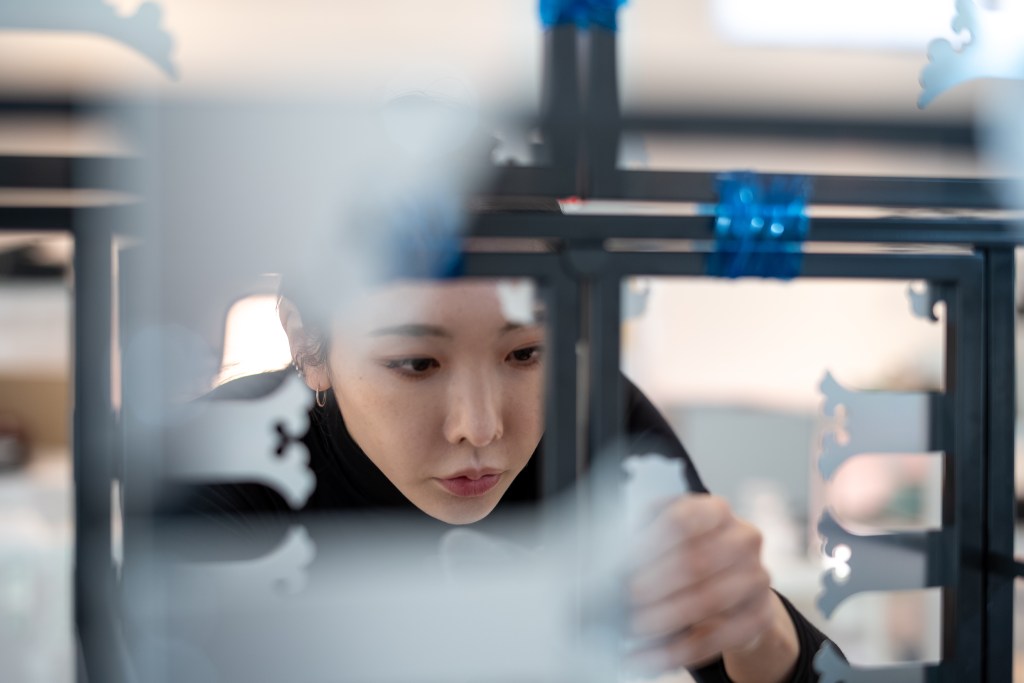

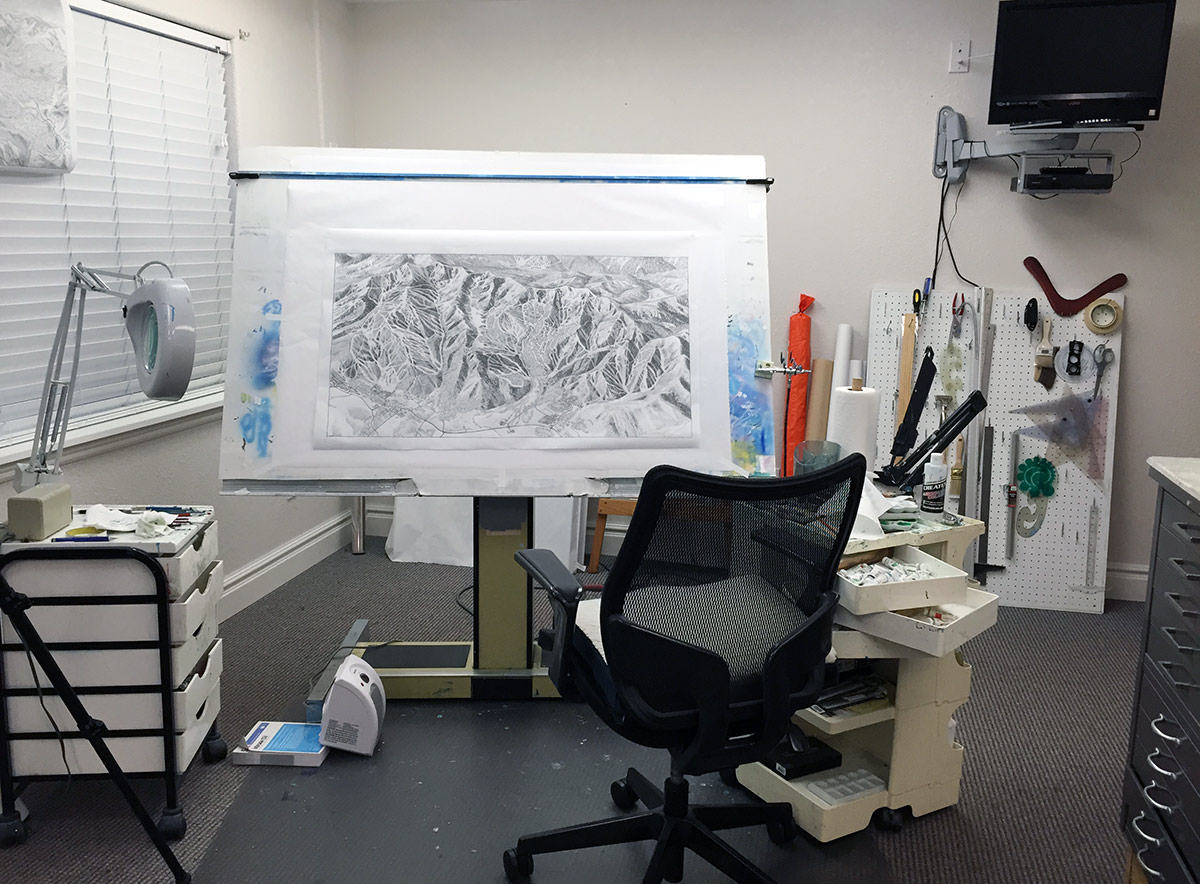

Then once that’s developed, I’ll just get an image through the computer and I’ll project that up on a paper that size, and just rough in what I’m doing, and then from there I’ll take a vellum, put it over the top, and looking through it I’ll go through it and start referencing my photographs, and finish in each area as I come down the mountain. So by the end of the time I’ll put in the towns at the bottom—the things I don’t like to do so much, buildings. I like the mountains.

Once that’s done, it goes out to the client for approval. I just got something back, that was really thorough—most people don’t send something back that’s this thorough—for Solitude. He’s coming back and he’s marking it up and telling me what to do in those areas, what he wants changes. There’s some new cuts that they’re putting in that I couldn’t see. Lots of times you won’t see cliff bands from the air, and they have an awful lot of slopes with cliffs in them. So he’s going in and sort of guiding me on where he wants me to put them. And then they make comments like an area isn’t steep enough, make it steeper; or they want to see a certain peak higher—different things like that.

What’s the shelf life of a map? With changing landscapes, how often must they be updated?

There are still some Bill Brown’s out there. I painted Mammoth in 2008, so they can have a long shelf life. And nowadays, there will be alterations made on mine—and I won’t even know it. It could just be some graphic artist putting in a trail. That happens a lot. There’s no way to police it. There’s a few out there, that I’ve called the ski areas, and told them to take my name off, and it’s been changed so many times and it’s been a horrible job, it doesn’t look like my work. And some of them will try to make a winter one into a summer one, which doesn’t work.

I saw a post you wrote about drawing different types of trees. So that’s important too?

Yes, I think it’s important that the skier know what kind of terrain he’s skiing through. Plus, you can identify what kind of forest you’re in. So the deciduous trees and the conifers are important to distinguish.

How else can you distinguish what kinds of terrain?

I will use a technique on some mountains, now that I’ve gotten into the satellite views a little more, not so much, but you’ll see the conifers are bluer in the distance, and as you get closer, they’re greener, and that’s generally what I do now. I used to use a technique where I did the top of the mountain in blue, and as I got down to the bottom of the mountain, it would be the greener, warmer colors. I’ve used another technique, like on Heavenly, which was the first satellite view that I did, and what I did on that one was use very warm colors on the top of the mountain, and use cool colors in the valley, because warm comes forward and cool recedes. I have some runs on that that are actually running up-page, and you look at it very quickly, and they’ll know which is up and down, just by the color relationship.

Do you think that you have to be hand-painting to get the right results?

I think so. I mean, I can’t imagine doing that with a computer. The thing of it is, whenever I talk to this other artist, he’s spent as much, or more, time on the computer as I do painting it. I think there’s a mental thing that “computer’s better, computer’s easier,” but I can envision this whole map just by flying it, and I’ve got it in my head. I know how it should be. We have an amazing tool in our own brain, and we ought to use it. Sometimes we get kind of lazy, and depend on the computer, and it baffles me that big ski areas will use inferior images for their trail maps. A computer-generated image just doesn’t have any romance to it. I think with an interpretation, the slopes look better than they actually are, in most cases.

Are you a skier?

Whenever I first got into this business, I was not a skier. In fact, Alta has an interesting story behind it. When I did Alta, it was one of my first ones, and so I went out and skied the mountain—but I couldn’t really ski. So I went up to the top of Collin’s lift, barely got down. They’d had six inches of snow the night before. Here’s an inexperienced skier trying to get down that mountain with an instructor, and I’m catching my edges, and it’s rough, I’m falling every 100 yards. And the instructor finally got upset with me and says, “You’d think, that a guy who does trail maps could ski!” Nope, I couldn’t.

Is there an area that you love most or find particularly beautiful?

It’s hard to beat the scenery of Alta, and Snowbird. Snowbird is one of my favorite paintings. It’s a dynamic area. Also, you get up to Washington, that’s really dynamic up there. Another one of my favorite paintings is Crystal Mountain—it has Mt Ranier in the background, and it’s just, wow. You get back east, there’s some mountains back there I really enjoyed doing: Killington. They are not as rugged as ours in Colorado, but they’re beautiful mountains.

Images of artwork courtesy of Jim Niehues, studio images by Kelly O’Reilly