The DNA of Things

Italian designer, artist, engineer and researcher Maurizio Montalti crosses the boundary between nature and culture

by Stefano Caggiano

Italian multidisciplinary designer, artist and engineer Maurizio Montalti is the founder and director of Officina Corpuscoli, a laboratory of scientific creative research dealing with the role design could play in the bio-tech revolution in relation to sustainability. Montalti’s interesting career path was undoubtedly shaped by his education at the Design Academy in Eindhoven, one of the world’s most influential design schools and renowned for its focus on working around the boundaries between different fields—not only to go out of the box but to warp the box itself. This way of thinking is evident in Montalti’s work.

The state of design today is arguably similar to the time when Einstein introduced the theory of general relativity and altered the concept of matter in space. In such a scenario, Montalti uses micro-organisms to create or modify objects, like in the projects “Symbiosis,” “Symbiotic Jewelry,” “Infected” and “SuperOrganism,” for which he tested what happens when the distinction between nature and culture melts down and designers are able to make the matter “naturally” produce pieces of culture.

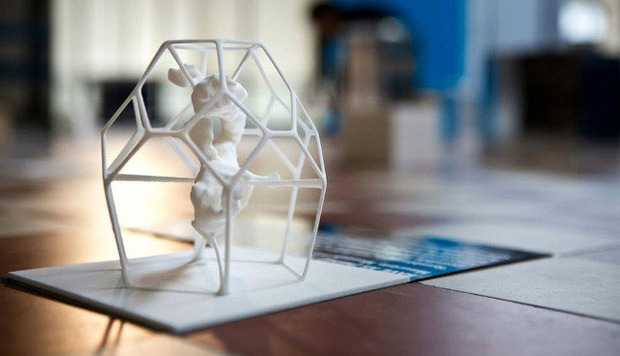

The philosophical core of Montalti’s research is connected with the ongoing revolution ignited by 3D-manufacturing, which he himself uses with fungi as a printable material. Because traditional fixed matter requires designers to outline shapes to contain it, 3D-printing makes them able to design the very DNA of matter and make it emanate its own shape. Rather than working with the tangible phenotype of things, designers can now have their hand in creating their very own genotype that sets the form matter has to grow into.

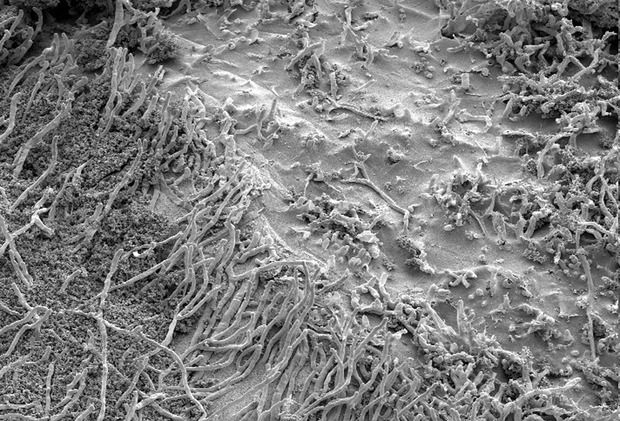

But the use of micro-organisms goes even further, by making design enter the other side of material existence, the disappearance, that in bio-cycles is as natural as appearance. Montalti’s “Continuous Bodies,” for example, consists of a shroud inoculated with fungal mycelia Schizophyllum Commune whose action favors the decomposition of a dead body, turning it into nutrient supply for surrounding life forms. While “Phanerochaete Chrisosporium” fungi—once implemented in a bio-cover—does the same with inanimate objects like plastic chairs or cutlery.

As Montalti puts it: “I use this chair as a statement about the life-cycles of consumer products in comparison with the immortality of the materials most of the consumer products are made of. Highlighting the complementarity of life and death, with my design, the “Bio-Cover,” I play with the idea of infusing life in a dead everlasting material, in order to trigger a process of final dissolution.” The word produce comes from the Latin “producere,” which means “pushing something out of nowhere.” But in a world where goods saturate the mental horizon of seduction—in the literal sense of “pushing them out of being” it becomes as important as “pro-ducing.”

People concerned with the project are then likely to be increasingly called in to design not only the being of things, but also the inexistence of things. Pollution and a shortage of energy are a consequence of the sharp separation between culture and nature, that left the latter as a sort of free container where you can put all kinds of things. According to Montalti we have to recognize “how important it is to team up with other species and organisms and establish with them a symbiotic relationship.” Focused on material composites and objects grown from fungi, this strategic research will keep him and his team busy for the next three or four years.

For decades, design only took care of the tech-side of the project, and now the time has come to take care of its bio-side, through the use of the new technologies that enable designers to manage the very DNA of things, not to put the matter (nature) inside the form (culture), but to set them growing up as a whole.

Images courtesy of Maurizio Montalti