Alfred Steiner’s “Likelihood of Confusion” Exhibition

Iconic logos reconstructed through found imagery at Joshua Liner Gallery

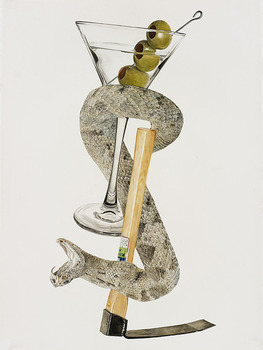

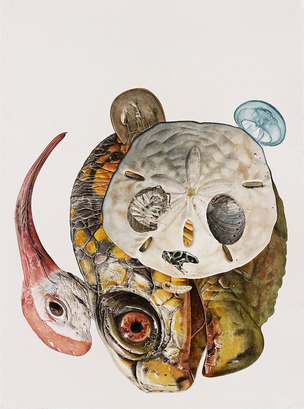

There’s something uncanny about Alfred Steiner‘s latest exhibition “Likelihood of Confusion,” now on display at NYC’s Joshua Liner Gallery. There’s an element of deep recognition and familiarity to each work, but an exploration within reveals numerous components that add further dimensions and question the piece as a whole. Steiner had a view in mind to tackle the pervasiveness of media and advertising. And he did so by taking logos and trademark imagery and building something similar based upon found photos. Steiner calls iconography into question across 12 works of watercolor on paper, two oil paintings on medium-density fiberboard, and a new piece within his celebrated “Anti-Paparazzi” series—from their resonance and value to the very idea of trademarking.

There’s a lot to be said about titles of exhibitions, and with this show, Steiner hints at his background in law. “Likelihood of confusion is the legal standard used in trademark infringement cases,” he shares with CH. “If potential customers are likely to confuse one business’ trademark with the pre-existing trademark of another business, then the owner of the pre-existing trademark (or senior user) is entitled to stop the later (or junior) user from using the trademark on its goods or in connection with its services.” Delving further into the legal nature of such a title reveals how Steiner’s art is protected and also hints to other interpretations viewers may have. “Two primary factors used to make this determination are the similarity of the marks themselves and the relatedness of the goods or services. As used for the title of the show, ‘Likelihood of Confusion’ carries the superficial suggestion that the compositions of the works are structured by trademarks, but it may also signal other things, like the perplexity that viewers may face when trying to understand the works or when trying to understand contemporary art more broadly.”

“I was one of those kids who was always into art. I took as many art classes as I could in middle school and high school. In college, I shied away from majoring in art after my first art course took more time than all of my other classes combined, coupled with my perception that my parents, who were footing the bill, would have frowned on such an apparently impractical course of study,” the artist notes, regarding his background. “I went to law school because my other choice was to start work on a Ph.D. in the philosophy of mathematics, and that sounded too abstruse and solitary. In law school, I drew a cartoon for the Harvard Law Record called Reasonableman, featuring a title character who was anything but reasonable.” Steiner has never stopped painting or making things since.

“Law and art have been in most ways separate spheres for me. But there’s no question that the study of law has influenced my work,” he continues. “When I was deciding to go to law school, one of my friends suggested that I might be interested in intellectual property. I got a book about it from the library and I was hooked. The types of questions that come up in copyright and trademark law often parallel questions in art. Because I am familiar with the law in those areas, I often see possibilities for projects that might not occur to other artists.

As for what facilitated the artist’s desire to alter logos and imagery that have become globally recognizable, he shares that “using pre-existing imagery to structure my compositions began as a way to channel improvisational drawings. At first, I used geometric figures and then I moved on to iconic art-historical sources. But I found that the sources that produced the most interesting results were graphic or stylized—cartoon characters, trademarks and the like. And it seemed to me, as it still does, that dissecting these pervasive graphic images the way I do might serve some valuable form of visual research, however nebulous and indeterminate.”

Steiner, inspired by the pull of graphics, begins by dissecting them. “I look at my source image, say the Starbucks logo, and I free-associate based on the shapes it contains. Some possibilities readily occur to me, but with others, I might draw a shape over and over, invert my sketchbook and even ask other people what a particular shape reminds them of.” From there, the internet takes over. “Once I have an idea in mind, say a Greek vase for the body of the Starbucks siren, I do various image searches, looking for something that will best fit the contours of my image. Sometimes, I have to abandon an idea because I can’t find a good model.”

Using such found images also toys with the idea of copyright. There simply aren’t a lot of color images in the public domain, but Steiner is never seeking an image as whole, but rather independent elements within. “What I am looking for are essentially visual facts—an apple, a bottle of whisky, an alligator skull. When divorced from the rest of a photograph, whatever creative element the original photographer added becomes difficult to identify—there are only so many ways to photograph an apple in a matter-of-fact manner. And once these visual facts are organized in my composition, their aesthetic import changes dramatically. I’ll say they are ‘transformed’ to use a copyright word that has come to dominate the fair use discussion.”

“Likelihood of Confusion” will be on display through 15 November 2014 at NYC’s Joshua Liner Gallery.

Images courtesy of Joshua Liner Gallery